Chianti and The Black Rooster

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Chianti From the Romans, the Renaissance and Today

Tuscany, the romanticized area of central Italy known for its rolling hills, cypress trees and stone castles, is also home to Chianti.

The Chianti region of Italy, located in Central Tuscany, is one of the most beautiful areas in the entire region.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Tuscany is dreamy and romantic picturesque area of Italy, featuring lush, rolling hills, gorgeous villas and a tribute to days gone by.

Tuscany is also well known for the wines that come from the region – Chianti.

Chianti is a medium-bodied mouthwatering, acidic red wine with moderate to high levels of tannins.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – While the wines from this area are diverse, they share a few of the same flavor notes.

Chiantis tend to be floral and spicy when young and develop earthier notes as they age.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Some of the History of Tuscany

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Its history stems from the Etruscans, who were the first to identify the region as an attractive source for grapes.

The Romans further developed the area’s agriculture, which also included olives.

Wine has been produced in the Tuscany area since Etruscan times, and as far back as 1398, legal documents mention Chianti wine.

In 1716, Cosimo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany, defined the geographical area.

This, however, did not stop the emergence of bogus producers of wine claiming that their wine vintages to be Chianti.

Over 100 years ago, Barone Ricasoli organised a ‘Consorzio’ of wine producers to discipline itself.

The Barone’s descendents live in the Castello di Brolio, which dominates the southern Tuscan hills.

In 1924, in Radda in Chianti, a voluntary group met to promote and authenticate wine.

That organization is now known as ‘Consorzio del Marchio Storico-Chianti Classico.’

Each year the Consorzio validates the grape varieties and yields of its members’ vineyards and issues the famous ‘Gallo Nero’ symbol to the producer.

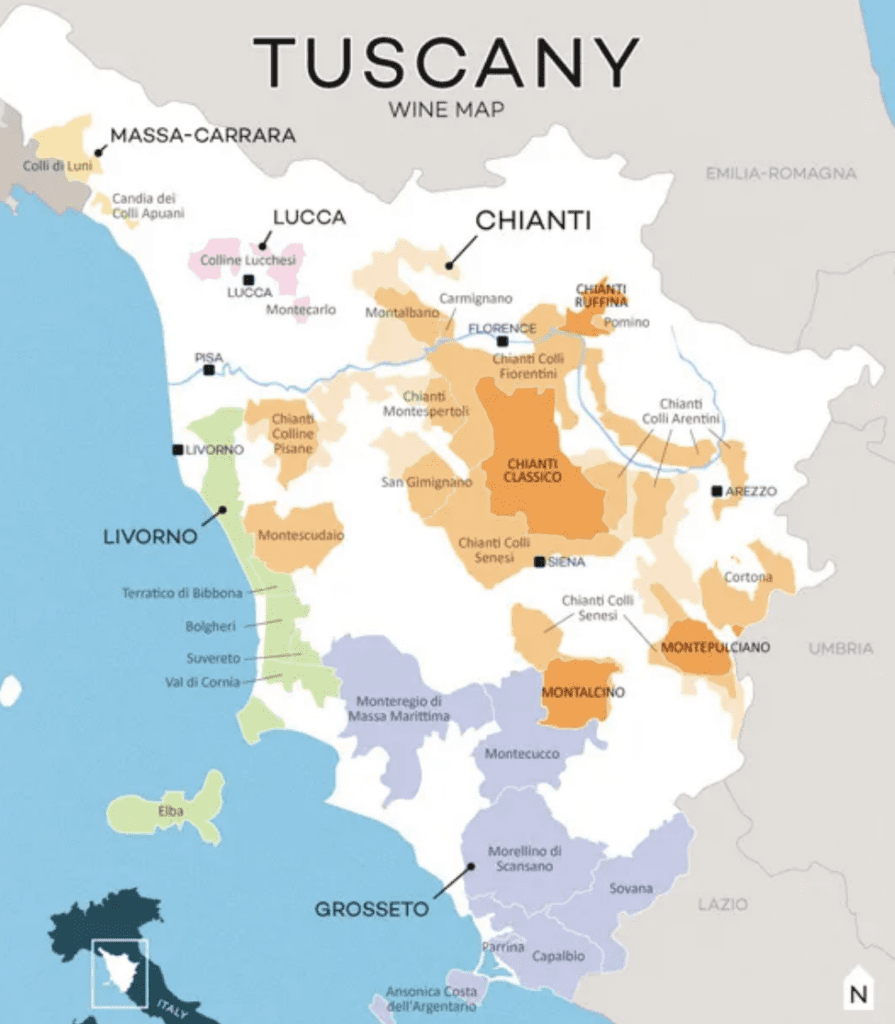

Today, the production zones of Chianti fall around Florence in the north, Siena in the south, Arezzo in the east and Pisa in the west.

These cities’ histories are as rich, complicated and lurid as a Shakespearean drama.

What Wine Drinkers Need to Know About Florence and Siena

Chianti and The Black Rooster – It all ends with the legend of the Black Rooster as the symbol of Chianti Classico.

THE LEGEND – White vs black roosters were used to settle a territory boundary issue.

The story of the Black Rooster in Chianti is based on the war between Siena and Florence

From the Wine Drinker’s Perspective, Here’s What You Need to Know About the Origin of the Black Rooster & Why the Rooster is Black and Not White

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Florence and Siena had a long history of battles.

The cultural and historical impact of Florence (or Firenze) and Siena are overwhelming, but close up, both cities are some of Italy’s most atmospheric and pleasant, retaining a strong resemblance to the small late-medieval centers that contributed so much to the artistic and political development of Europe.

Even long after their decline on the political and economic horizon, Florence and Siena upheld their elegant appearance: their skylines, that include medieval towers, russet rooftops, lofty domes, striking buildings, formidable galleries and treasure-crammed churches are indeed picturesque and incredibly romantic and fascinating.

During 13th and 15th centuries the economic and military power of both cities grew enormously and inevitably friction grew between Siena and Florence, as both tried to enlarge their territory.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – There were many battles between the two cities between the 13th and 15th centuries, some won by Siena, but eventually Florence had the upper hand and Siena was incorporated into Florentine territory and administration.

Firenzie and Siena’s Boundary Issue

Chianti and The Black Rooster – The Black Rooster symbol is linked to a medieval legend that takes place during the time of open hostilities between Firenze and Siena for control of the Chianti territory.

In Medieval times, Florence and Siena went through many bloody battles over who should rule the hills of Chianti.

In fact, so much blood was shed that they finally decided to settle this once and for all, so they came up with a rather unique way of doing it.

As the battles for territory continued in the 14th century, a competition was held between Florence and Siena to determine, once and for all, the boundaries of each city-state.

To end this ancient dispute and establish legal political boundaries, both cities came up with an idea of an unusual race, knights would depart on horseback from their respective cities at sunrise and fix the boundary between the two city-states at the point where they met and that point of intersection would be declared the legal border.

The only alarm clock available in the day to wake up the riders was the roosters cock-crow.

The Sienese selected a beautiful, white rooster, raised sleek and fat with the idea that it would loudly wake their knight at dawn.

The Florentines kept their black, malnourished black rooster in a small, dark chicken-coop and did not feed it for days.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – On the day of the ride, once the black rooster was freed, it began to crow well ahead of dawn, allowing for the Florentine knight to depart well in advance of the Sienese knight – as the white rooster had not crowed.

Because the hungry Florentine rooster awoke very early it allowed the Florentine horseman to cover much more ground than did the Sienese one who departed much later.

The two knights met in Fonterutoli, only 12 km from the point of departure of the Sienese knight.

This allowed Firenze to control nearly the entirety of the Chianti territory – giving Florence rule over the majority of the Chianti Classico area.

In this way, almost all of the Chianti was under the role of the Florentine Republic and the black rooster much celebrated.

As a direct result artist and writer Giorgio Vasari painted a black rooster on the ceiling of the Palazzo Vecchio, and the Consortium chose the Gallo Nero as their symbol.

The Gallo Nero (Black Rooster) was the historic symbol of the League of Chianti and has become the symbol of the wines of Chianti Classico.

The Black rooster still commands the square of Gaiole in Chianti

Towards the end of the 14th C. the Lega del Chianti, Chianti League, a political and military alliance was created to administer and defend the Chianti territory for Florence. The league’s coat of arms featured the black rooster on a field of gold, a symbol still associated with the Chianti Classico to this day.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Ever since this day, the black rooster has become a well-known symbol for great quality wine and Florentine victory.

The History of The Chianti Symbol

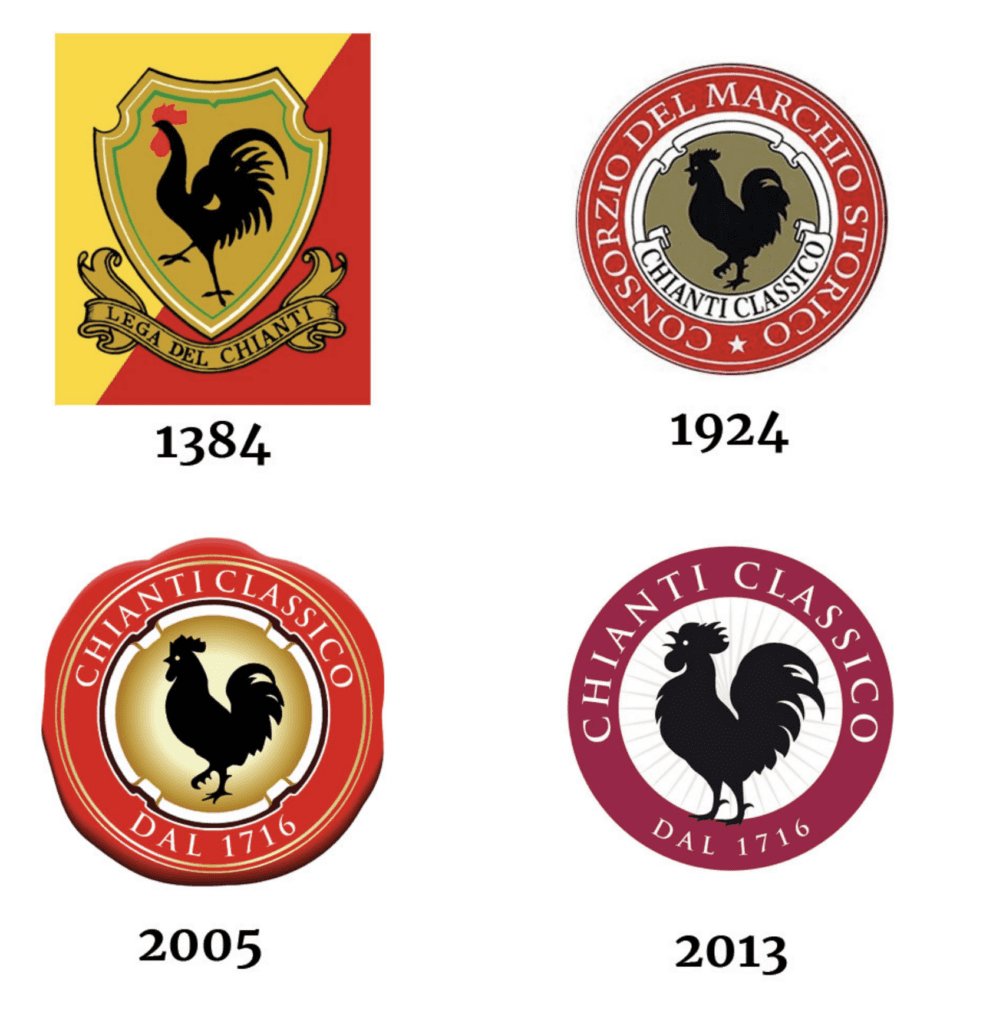

Chianti and The Black Rooster – The image of the Black Rooster has evolved over the years; from the original symbol of the Lega del Chianti to the emblem that was in use during most of the 20th century (where the nomenclature has been changed several times), followed by the one that entered the scene in the early 2000s, and last, but not least, the present one that was redesigned in 2013.

The Evolution of The Chianti Symbol

The symbol dates to the Middle Ages when the Lega del Chianti, a political and military institution created by the Republic of Florence to control the Chianti area, used it.

Historically, the black rooster crest belonged to the League of Chianti, founded in the 13th century.

In the Middle Ages the rivalry between the Tuscan town of Florence and Siena was legendary.

In 1967 the decree recognizing a single Denomination of Controlled Origin (D.O.C.) of the Chianti enters into force, within which the “Classic” is disciplined as a wine with more selective characteristics.

The 1984 specification provides that “Chianti Classico” wine must be obtained from grapes produced in the production area and from vineyards with Sangiovese grapes for a minimum of 80%.

In 2005 the symbol was adopted from the Chianti Classico Consortium founded in 1924 in Radda in Chianti as a reaction of producers to a decree that essentially punished Chianti, negating the link between the denominations and geographical origins.

The Black Rooster is a very important symbol for all Chianti Classico producers.

When it is placed on the neck of a bottle, or on the label, it makes it possible to distinguish a wine that has been produced within the territory of Chianti Classico (a Chianti Classico wine) from those that have been produced outside of the Chianti Classico territory, i.e., Chianti wines in Tuscany without the affix “Classico “ and without the Black Rooster.

The images to the left show how the logo has developed over the years; from the original symbol of the Lega del Chianti to the emblem that was in use during most of the 20th century (where the nomenclature has been changed several times), followed by the one that entered the scene in the early 2000s, and last, but not least, the present one that was redesigned in 2013.

Today, the symbol of Chianti Classico is the silhouette of this “Gallo Nero,” or black rooster on a white background with a burgundy border encircling it.

The symbol is designed as a black rooster on a white background with a burgundy rim for Chianti Classico and a golden rim for Riserva, a higher grade.

Today, Chianti Classico is an autonomous DOCG with its own production disciplinary distinct from that of Chianti.

The vinification, storage and bottling operations must take place exclusively within the production area and may be released for consumption from 1st October following the harvest.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Tuscany’s Chianti Wine Regions

Chianti is a century old wine region in Tuscany and houses around seven sub-zones producing classic wines from Sangiovese, the main grape variety of the blend. Chianti Classico is the genuine gem of the region which stretches between Florence and Siena.

Chianti Sub-Regions

Panoramic views of rolling green hills dotted with olive groves and vineyards are abundant in all of the main Chianti sub-zones.

Yet when Chianti was first demarcated in 1716, it included only 3 villages: Gaiole, Castellina and Radda.

In 1932 the growing zone was completely redrawn and subdivided into 7 areas. These sub-zones are:

Colli Fiorentini, the hills just south of Florence Rufina, around the comune of Rufina, north-east of Florence on the southern edge of the Mugello Classico, the heart of Chianti, covering the famous hills between Florence and Siena Colli Aretini, to the east in the province of Arezzo Colli Senesi, just south of the Classico sub-region, close to Siena Colline Pisane, the farthest west of all sub-zones, in the hills close to Pisa Montalbano, north-west of the Colli Fiorentini, close to Prato Chianti nowadays has 8 sub-zones, because part of the Colli Fiorentini were renamed Montespertoli in 1996, with the town of the same name now at the centre of this growing area.

Each Chianti sub-zone creates a unique expression of Chianti wine, with differences including how long they age, how much alcohol they contain, and which regional dishes they best complement.

The most famous area of them all is Chianti Classico.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Chianti Classico, Chianti and Its Subzones

Like all Italian wines, Chianti comes with rules.

And like all Italian rules, they are frequently confusing.

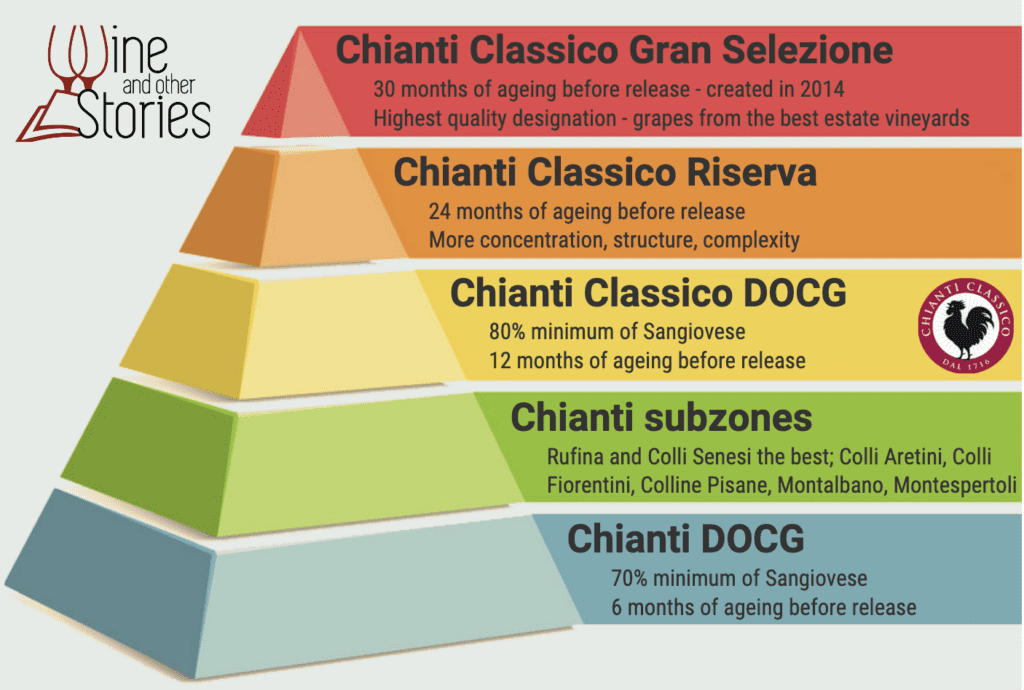

There are several categories of “Chianti.” There’s Chianti, which is the catchall appellation at the bottom of the quality pyramid; Chianti Classico, which has its own appellation; and Chianti Rufina and Chianti Colli Senesi, sub-zones of Chianti known for their high-quality bottlings.

The earliest examples of Chianti were a white wine but gradually evolved into a red.

Baron Bettino Ricasoli, the future prime minister in the Kingdom of Italy created the first known “Chianti recipe” in 1872, recommending 70% Sangiovese, 15% Canaiolo and 15% Malvasia bianca.

Chianti then evolved slightly with a blend of 70% Sangiovese, 15% Canaiolo, 10% Trebbiano and Malvasia and the remaining 5% complementary vines, including Mammolo and Colorino.

The “blend” of Ricasoli was immediately successful, so much so that in 1878 the Chianti won the first gold medal at the international exhibition in Paris.

The characteristic of Ricasoli wine, beyond quality, is to be rich in scents and flavors and to be authoritative for its character.

It was born to be poured and sipped calmly or to accompany a roast, but it lent itself very well to be enjoyed with satisfaction even with the typical Tuscan cold cuts.

With its peculiar organoleptic characteristics, it represented that part of Italian nobility that was at ease with both royalty and simple people.

Chianti DOCG

Chianti Classico DOCG is the heartland of the Chianti wine region – its traditional and longest-established viticultural area.

The typical Chianti Classico wine is a ruby-red, Sangiovese-based wine with aromas of violets and cherries and a hint of earthy spice.

The Chianti DOC title was created in 1967, and in 1984 the region was promoted to the highest level of Italian wine classification: DOCG.

The area’s most highly regarded wines come from the Chianti Classico zone, which was awarded a separate DOCG status in 1996.

As in other Italian regions, the Classico designation roughly corresponds to the original (and so theoretically the best) area of production in the Chianti hills, first codified in the early 1700s.

The modern-day Chianti Classico viticultural area now covers almost all land between Siena and Florence.

It is buffered at each end by the Colli Fiorentini and Colli Senesi production zones.

The other demarcated Chianti zones are Colli Aretini, Colline Pisane, Montalbano, Montespertoli and Rufina.

The latter is the only one generally considered to rival the quality of Classico vineyards.

The term classico is used in this way in several Italian wine regions (Orvieto and Valpolicella, for example), although Chianti is the most famous example.

Since 1996, the rules of Chianti’s broadest appellation require a minimum of 70% Sangiovese and a maximum of 10% being the white grapes Malvasia and Trebbiano.

Native red grapes like Canaiolo Nero and Colorino, as well as the international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah are also allowed.

These add fruit, tannin or softness to the final blend.

Chianti DOCG Seven Sub-zones

Chianti Colli Aretini

Chianti Colli Fiorentini

Chianti Colli Senesi

Chianti Colline Pisane

Chianti Montalbano

Chianti Montespertoli

Chianti Rufina

Grapes from across the region (but excluding the Chianti Classico zone) can be blended into the wine.

Chianti is meant to be consumed while young, bright and fresh. Chianti DOCG has two higher-quality categories: Superiore, for wines made from lower yields than straight Chianti, and Riserva, for wines aged at least two years before release.

Chianti DOCG is divided into seven subzones: Chianti Rufina, Chianti Colli Aretini, Chianti Colli Fiorentini, Chianti Colli Senesi, Chianti Colline Pisane, Chianti Montalbano and Chianti Montespertoli.

Wines made in these areas may choose to use the name of their subzone or simply be labeled as Chianti.

Of the seven sub-zones, Rufina and Colli Senesi are the most available in the U.S..

Chianti Rufina

Chianti Rufina is considered one of the smallest but also one of the most quality-driven zones, behind Chianti Classico.

Rufina is furthest from the coast, and boasts higher-elevation vineyards thanks to its location in the foothills of the Apennine Mountains.

Rufina is small by comparison, with production of around three million bottles each year.

Chianti Rufina is the most famous of the seven subzones that fall under Italy’s iconic Chianti DOCG.

The area, in the hills to the east of Florence, has a more continental climate and higher altitude that makes a Sangiovese-based wine in possession of good tannins and acidity: closer in style to the prestigious Chianti Classico DOCG than its contemporaries.

The area, along with Montespertoli southwest of Florence, is one of the smallest of the subzones in Chianti.

It covers land around the small town of Rufina on the banks of the Sieve river, in the foothills of the Apennines mountains.

Rufina is a little way removed from most of the rest of Chianti, and is the farthest inland – although it does share some of its border with the Colli Fiorentini sub-zone. Chianti Rufina overlaps with the Pomino DOC to the east, which specializes in white wines based on Chardonnay and Pinot Bianco.

Both altitude and distance from the coast play big parts in the terroir here.

The vineyards rise up as high as 500m (1600ft) above sea level, much higher than the average altitude of 300m (1000ft) in Chianti Classico.

Its cooler climate allows slower ripening of Sangiovese. With a substantial difference between day and night temperatures, Rufina retains its acidity and lovely perfume, though wines can be hard and angular without sufficient fruit to bolster them.

As a part of Chianti DOCG, Rufina must contain at least 70% Sangiovese, with the remainder blended with Canaiolo, Colorino or international red varieties.

In style and substance, Chianti Rufina mirrors Classico with its vivid fruit and juicy acidity, along with a tannic structure that lends itself to five to 10 years of aging, especially from the best vintages and producers, or along the higher Riserva tier.

Chianti Colli Senesi

It takes its name from its location on the hills that envelop Siena in southern Tuscany.

Chianti Colli Senesi is perhaps Chianti’s most significant subzone, located on the hills surrounding Siena in the southern part of the Chianti region.

The area overlaps some of Tuscany’s most famous wine names – Montalcino, Montepulciano and San Gimignano – with the Chianti Colli Senesi title used to cover Sangiovese-based wines from the less prestigious vineyards of the area.

One of Chianti’s seven subzones, it is the largest after Chianti Classico of which it wraps around the southwestern edge of.

It is divided into three noncontinuous sections, stretching as far north as San Gimignano, where Tuscany’s only white DOCG is found, Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

The other two sections cover area around the cities of Montalcino and Montepulciano.

Its proximity to the Tuscan DOCGs of Brunello di Montalcino and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano leads to occasional overlap, which adds excitement about Colli Senesi’s prospects of quality.

Variation in elevation and soil gives nuance to these Senesi wines, though overall, they tend to be fruit-forward and approachable with a touch of rusticity.

New oak and barrique are typically not employed, in favor of purity, spice and fruit in the wines.

Chianti Classico DOCG

This appellation is located in the heart of the broader Chianti region.

The boundaries were first defined in the 18th century, but enlarged significantly in the 1930s.

This move was thought by many to have damaged the brand’s reputation, though such expansion is common across Italian wine regions.

Today, Chianti Classico DOCG is considered by many to be the highest-quality offering for Chianti.

The emblem of Chianti Classico is the black rooster, or gallo nero.

It relates to a legend told about the use of roosters to settle a border dispute between the warring provinces of Sienna and Florence.

The black cockerel was the symbol of Florence, while the white cockerel represented Sienna. It’s clear who dominated that contest.

Marked by refreshing acidity, Chianti Classico DOCG grapes come typically from vineyards planted at higher elevations than Chianti DOCG.

Flavors include violet and spice layered atop juicy cherry. Tannins and structure increase with quality, but reflect fruit and terroir rather than oak.

New oak, which can slather wine in baking spice and vanilla, has mostly been abandoned.

Traditional large oak casks are now preferred, which lend greater transparency to wines.

Chianti Classico DOCG Nine Communes

Barberino Val d’Elsa

Castellina in Chianti

Castelnuovo Berardenga

Gaiole in Chianti

Greve in Chianti

Poggibonsi

Radda in Chianti

San Casciano Val di Pesa

Tavernelle Val di Pes

The Black Rooster appears against a red background on Chianti Classico and against a gold background on Riservas.

The Riservas will have a minimum alcohol content of 12.5 percent (12.0 percent for the Chianti Classico) and be aged for 27 months.

Better quality vines are used for the Riservas, which can be aged for many years, but, of course, they are considerably more expensive than the Chianti Classicos.

Today, Chianti Classico is an autonomous DOCG with its own production disciplinary distinct from that of Chianti.

The 1984 specification provides that “Chianti Classico” wine must be obtained from grapes produced in the production area and from vineyards with Sangiovese grapes for a minimum of 80%.

The vinification, storage and bottling operations must take place exclusively within the production area and may be released for consumption from 1st October following the harvest.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Chianti Wine Types

In 1716, Grand Duke Cosimo III de’Medici demarcated the first Chianti wine zone, now known as Chianti Classico.

Fast forward two centuries and production had grown throughout the region.

The Italian government created the Chianti Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) in 1967, which was included a central sub-zone of Chianti Classico.

However, Chianti’s success proved its undoing. In the 1970s, high demand led to a rash of vineyard plantings.

Rules that allowed or even required inferior grapes contributed to overproduction and underwhelming wines.

Prices and the region’s reputation plummeted, something many producers still battle.

In the late ’70s, a rogue band of quality-minded producers started to bottle wine outside the DOC’s approved grapes, which sparked the creation of super Tuscans. Eventually, Chianti’s rules were modernized to reflect contemporary winemaking and tastes and allowed a certain percentage of these international grapes, but with Sangiovese remaining dominant in the blend.

The appellation would go on to earn Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status in 1984, Italy’s highest level of wine classification. And in 1996, Chianti Classico separated from Chianti DOCG and became its own DOCG.

Combined, Chianti and Chianti Classico DOCGs continue to grow more wine grapes than any other Italian region save Prosecco, though better clones and a focus on lower yields have lifted quality.

There are a few different designations of Chianti available on the market, with the differences between them being based largely on the percent Sangiovese they contain, the area in which the grapes are grown, and the aging requirements.

Standard Chianti contains a minimum of 70% Sangiovese grapes.

The remaining 30% is typically a blend of Merlot, Syrah, and Cabernet though regional grape varieties such as Canaiolo Nero and Colorino may be found as well.

These wines have the shortest aging period before release, typically three to six months.

These thin-skinned fruits provide a transparent ruby color and flavors of cherries, plums, and dried herbs.

Upon aging, notes of earth and leather become apparent.

There are three quality tiers in the appellation.

Annata, or the standard wine, ages for 12 months before release, while Riserva must age 24 months.

Gran Selezione has the longest aging requirement at 30 months.

Sangiovese grapes also feature high acidity and excellent tannins.

Chianti Classico

Chianti Classico consists of at least 80% Sangiovese.

A maximum of 20% of other red grapes Colorino, Canaiolo Nero, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot may be used.

White grapes were banned in 2006.

Classico is aged a minimum of ten to twelve months before being released.

To be labeled Classico, the grapes must come from the Classico district.

This is the wine that carries the famous gallo nero or black rooster seal.

Since 2006, white grapes previously mandated for Chianti wine have been outlawed in the production of any Chianti that bears the Classico designation.

Chianti Riserva

Chianti Riserva undergoes a longer aging process of 24 to 38 months.

That extra time mellows the tannins in the wine and adds greater complexity and structure.

Chianti Superiore

Featuring Sangiovese grapes grown outside the Classico district, Chianti Superiore undergoes a minimum of nine months of aging. These wines also generally come from lower yields.

Gran Selezione

Created in 2014, Chianti Gran Selezione features grapes from the best estate vineyards.

The category also requires estate-grown grapes and approval from a tasting panel.

These wines undergo at least 30 months of aging before being released.

These are some of the highest-quality Chiantis available.

Chianti and The Black Rooster – Tips for Choosing Chianti Wine

Here are a few tips that may help navigating the selection process of a great bottle of Chianti for you a little easier:

Look at the blend.

Sangiovese is Chianti’s heart and hero. Its calling card is mouthwatering acidity, a transparent ruby hue and flavors of black and red cherry.

Further accents of violets, herbs, spice and earth are common in this dry red.

Moderate tannins increase with quality, as does structure and body, which progresses from light to medium.

Chianti rarely achieves the body and density of its Sangiovese-based cousin Brunello further south in Montalcino.

Many Chianti wines are blends of Sangiovese and other grapes.

The types of grapes that make up the remainder of the blend will add different flavors.

See how long the wine has aged.

Younger wines tend to be tart and fruit-forward, while aged varieties feature mellower tannins and more savory notes.

Consider what you’re eating.

Chianti wine makes an excellent accompaniment to different meals.

It pairs particularly well with pizza, pasta with tomato-based sauces, and rich meats.

Enough Italian To Survive In Italy >>

Enough Italian To Survive In Italy >>