Chicken

Get to Know Your Chickens

Get to Know Your Chickens

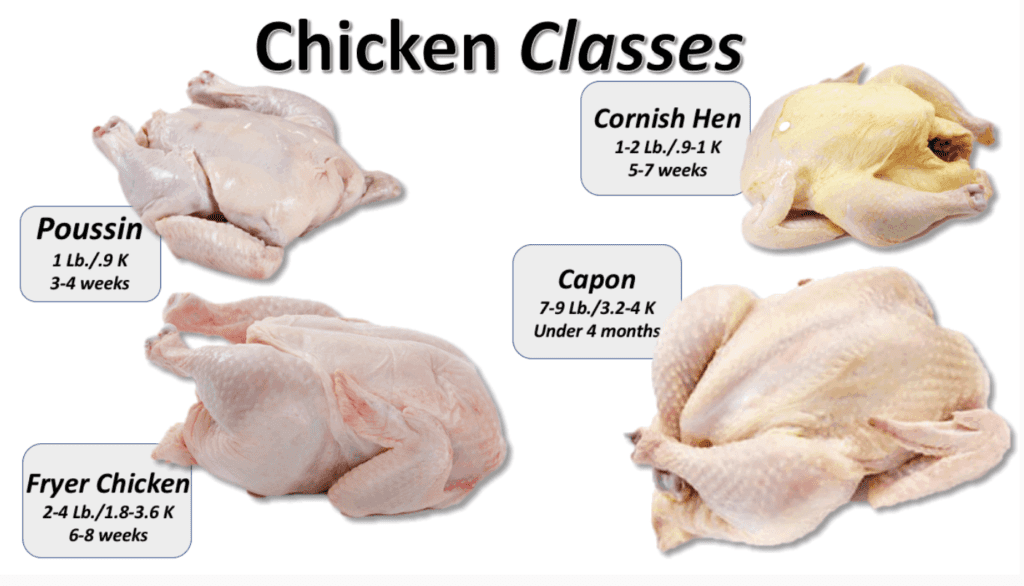

Broilers: Chickens 6 to 8 weeks old and weighing about 2 1/2 pounds

Fryers: Chickens 6 to 8 weeks old and weighing 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 pounds

Roasters: Chickens less than 8 months old and weighing 3 1/2 to 5 pounds

Stewing Chickens: Chickens (usually hens) over 10 months old and weighing 5 to 7 pounds

Capons: Castrated males that weigh 6 to 8 pounds

Cock/Rooster: Male chickens over 10 months old weighing 6 to 8 pounds

Get to Know Your Chickens – Broilers, Fryers & Roasters

Broilers, fryers, and roasters can generally be used interchangeably based on how much meat you think you’ll need. They are young chickens raised only for their meat, so they are fine to use for any preparation from poaching to roasting. You may need to adjust cooking times or amounts of other ingredients (like stuffing) based on what the recipe called for and the size of your chicken.

Get to Know Your Chickens

A broiler-fryer comes to market after six to eight weeks and weighs 3 to 4 lb., according to the National Chicken Council. The name reflects the fact that the young and tender meat is best cooked with high heat, making it the ideal bird to cut up or butterfly for the grill, broiler, sauté pan, or frying pan. The tender, mild-tasting meat and relatively small parts make them a poor choice for a stew or a braise, where they would tend to dry out. Left whole, a broiler-fryer makes a fine roast chicken, although the yield is a bit less than a larger bird—a 4-pound chicken barely serves four, while a 7-pound roaster can serve eight.

A roaster or roasting chicken is older—three to five months— and weighs 5 to 7 lb., according to the National Chicken Council. A roaster has a thicker layer of fat, which helps baste the bird as it roasts. The meatier parts are also fine cut up for stews or braises. But a roaster isn’t as good for grilling, broiling, or frying since the larger, thicker pieces will overcook (or burn) on the outside before cooking through. Also, it’s slightly tougher, more flavorful meat benefits from the slower cooking of roasting, braising, and stewing.

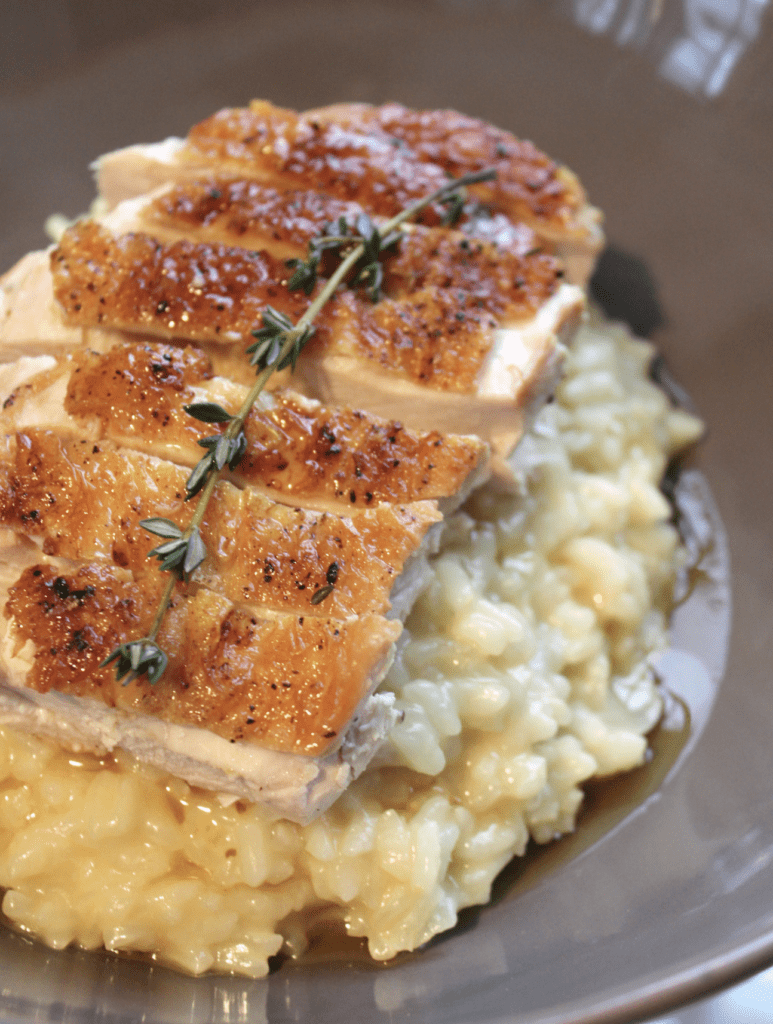

Dry Chicken in the Fridge

This step sounds kind of contradictory. The goal is to have the inside of the chicken moist and juicy but we want that lovely caramelized crust on the outside and that requires starting with the skin as dry as possible. Air dry the chicken out of the package in the fridge for up to four hours. Then, pat it down with a clean paper towel to soak up any remaining moisture.

Start With Chicken That is Room Temperature

Don’t start with an ice cold piece of meat fresh out of the fridge as this can lead to overcooking and uneven cooking. Ideally, let the chicken come to room temperature over an extended period of time a minimum of 20 to 30 minutes before cooking – if you throw an ice cold piece of chicken in a pan, the outside’s going to get dried out by the time the inside is cooked fully.

Start With a Hot Pan

Drizzle some canola or coconut oil in a pan and turn it up to super high heat (avoid butter here). High temperature is important to get a nice sear and caramelization. Avoid using extra virgin olive oil, which has a lower smoking point and will start smoking by the time your pan gets hot enough.

Next, lay your piece of chicken skin side down. After about eight to nine minutes on one side for your average bone-in thigh—obviously that estimate varies—flip it once. Then lower your heat to medium. For extra juiciness, add some fat—a pad of butter, more oil—when you flip your chicken and baste it, spooning the fat over the still cooking chicken. This will make for a moister final product.

Let The Chicken Rest

When it’s finished cooking, just like a good steak, chicken needs to rest. Once you have an internal temperature of 165 degrees, stop the heat and let it rest for few minutes before cutting, so the juices redistribute themselves back through the meat.

Poultry Production Methods

Since the 1950s, industrial production methods (and marketing) have more

than tripled the per capita consumption of chicken in the United States. In

more recent years, less industrialized production methods have gained

ground, leading to more choices

in the marketplace.

Get to Know Your Chickens – Free Range

Unlike mass-produced chickens, these birds have access to the outdoors. Unfortunately, the birds may not avail themselves of the opportunity to exit the access door and may spend very little time outside. Credible producers of freerange chickens raise their flocks outdoors for a specified time each day. The meat

of this type of free-range chicken may be slightly firmer and more flavorful than that of a cage-raised chicken, depending on how much exercise the bird gets.

Get to Know Your Chickens – Pastured

A more precise form of free-range production, pastured chickens live in outdoor pens that are moved from

field to field, providing them with a diet containing a high percentage of natural forage. The meat is firmer and much more flavorful than the meat of mass-produced chickens.

Get to Know Your Chickens – Organic

In the United States, organic chickens and their feed must be produced without the use of antibiotics, genetic engineering, chemical fertilizers, sewage sludge, and synthetic pesticides. An organic label can be given to mass-produced chickens that meet these criteria. Organic chickens are not necessarily raised free-range or pastured, but they must be given access to pasture.

Get to Know Your Chickens – Kosher

In accordance with Jewish religious law, kosher chickens are

raised and harvested humanely with strict bacterial controls. They must be slaughtered by hand by a certified kosher butcher and are salted for up to an hour to draw out their blood. The birds are then rinsed, but because they are still slightly saltier than other chickens, you should not brine them.

Get to Know Your Chickens – Four Other Kinds of Chicken

Capon — A surgically unsexed male chicken which develops more slowly and puts on more fat. A capon is about 16 weeks to 8 months old, weighing between 4 and 7 pounds. Capons are usually roasted and yield generous quantities of tender, light meat. Capons are great for roasting but can also be used for braises and poaching.

Poussin (pronounced “poo-sehn”) — A young chicken that is no older than 28 days when it is slaughtered. Sometimes called a spring chicken.

Stewing Hen — Stewing chickens are usually laying hens that have passed their prime, 10 months to 1 1/2 years old. They are older and their meat is usually tougher and more stringy. This type of chicken is best used in stews where the meat has time to break down during the long, moist cooking.

Rooster or Cock — A mature male chicken with low body fat and lean, ropey muscles. The skin is coarse skin and it has tough, dark meat, and requires long, moist cooking, as in the classic French dish, coq au vin. They’re rarely found in chain grocery stores, but can be found in specialty markets and many Asian markets.

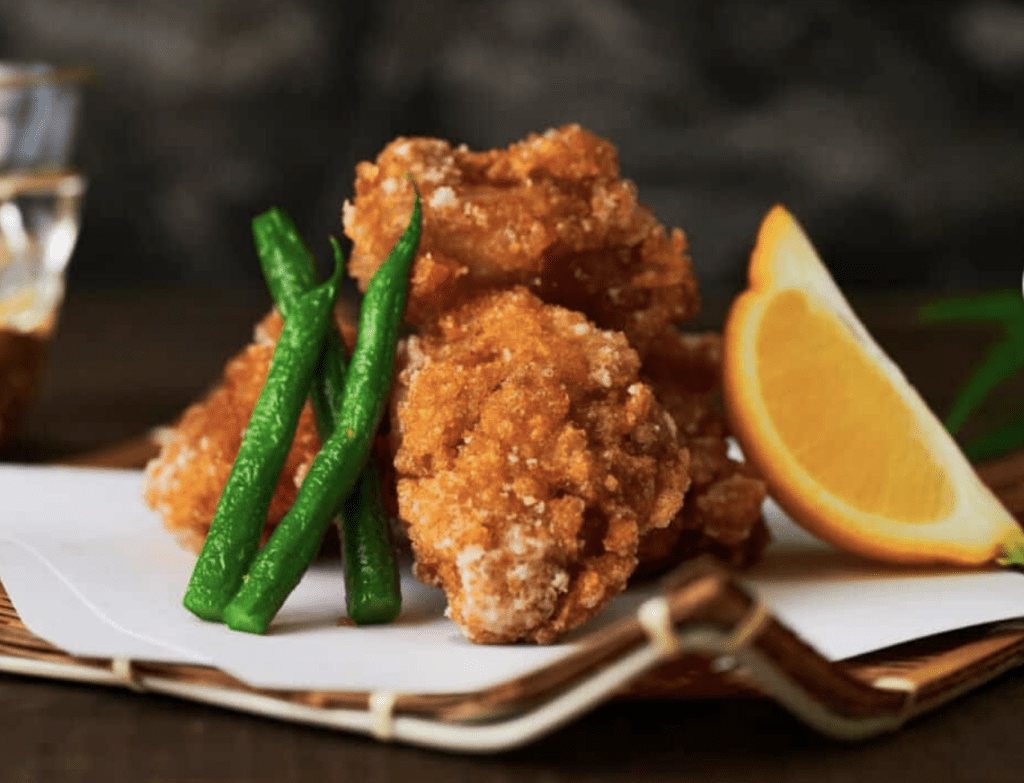

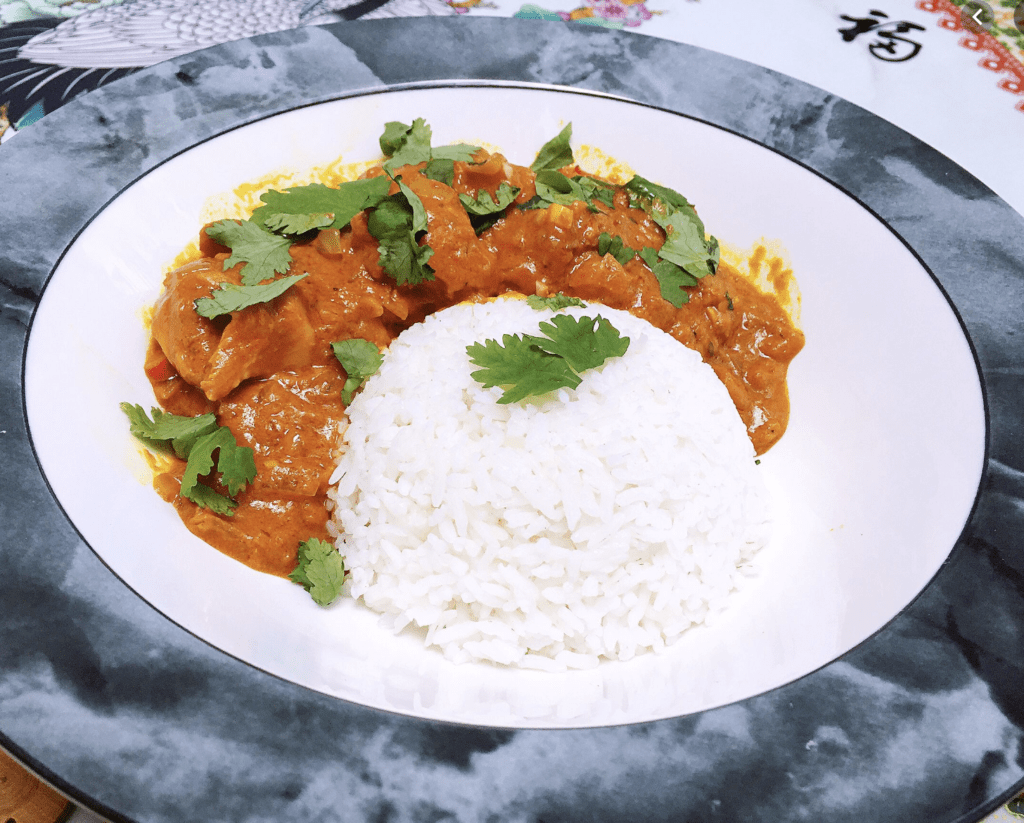

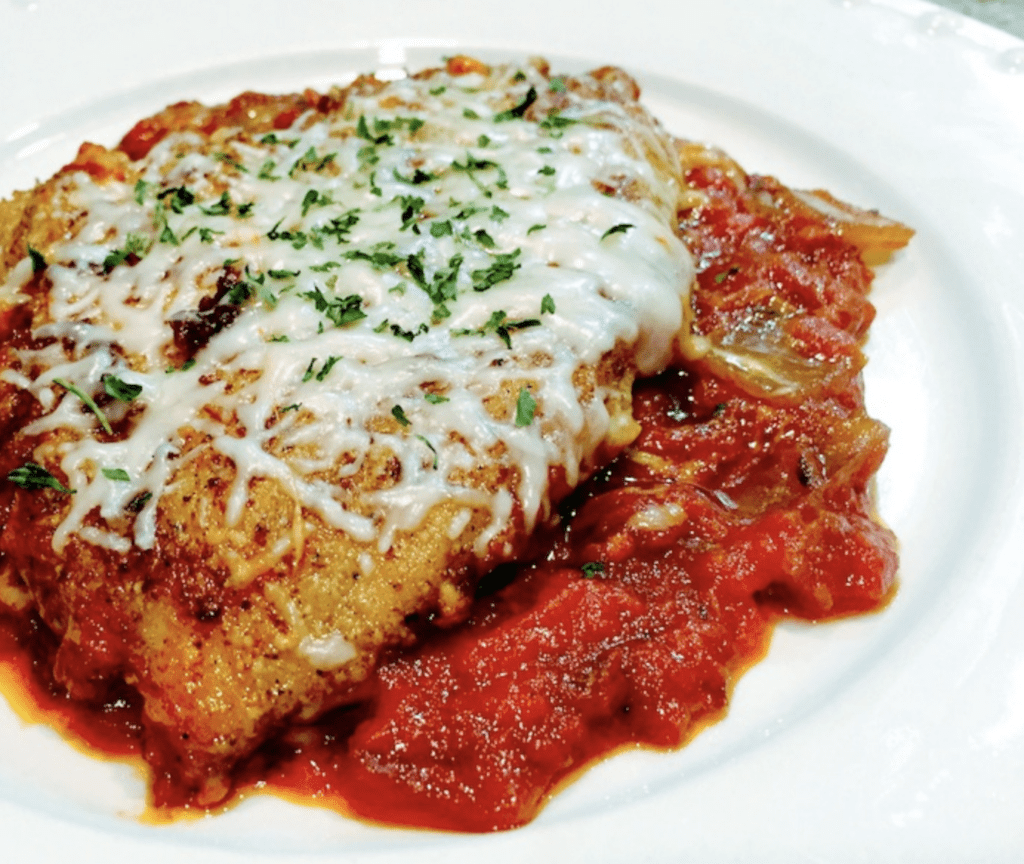

Gordon Ramsay Restaurants Chicken Recipes

Chicken Recipes from Gordon Ramsay Restaurants

Chicken & Autumn Vegetable Pies >>

Spicy Chicken Shawarma Wraps >>

Tray Baked Chicken With Butter Beans, Leaks Spinach >>